The Solheim Legacy: Why a Family Golf Company Still Matters in an Era of Eight-Figure Endorsement Deals

I’ve covered professional golf for 35 years, and I’ve watched the sport transform in ways both magnificent and troubling. We’ve seen equipment manufacturers turn into corporate behemoths, tour players become walking billboards, and—let’s be honest—the soul of the game get commodified in ways that would’ve made Karsten Solheim’s head spin.

Which is precisely why Michael Bamberger’s piece on Ping and John A. Solheim’s 30-year stewardship of his father’s company deserves more than casual reading. It’s a window into something increasingly rare in professional golf: a business philosophy where the equipment actually comes first.

The Pay-to-Play Pivot That Changed Everything

Here’s what struck me most about this story, and what I think separates Ping from nearly every other equipment manufacturer operating at their level: the deliberate choice to evolve without abandoning principle.

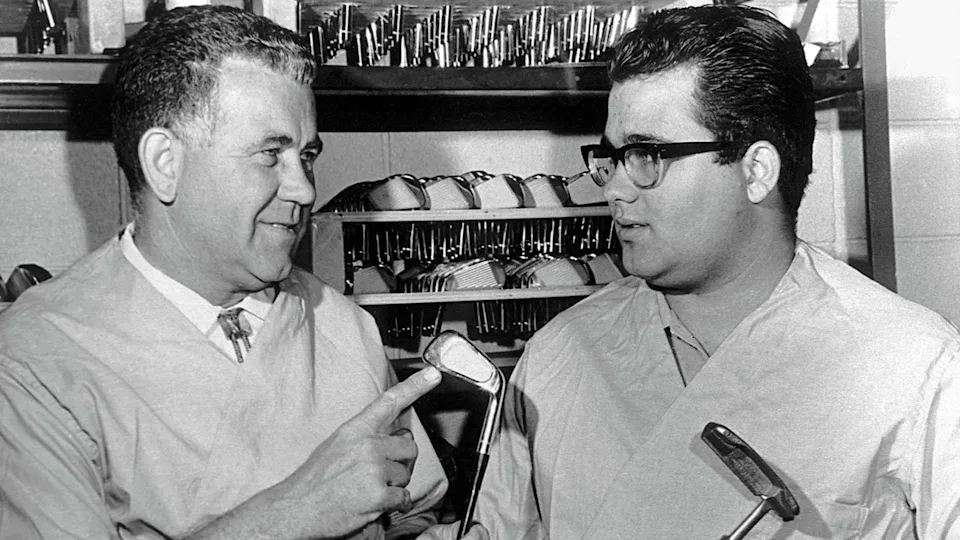

Karsten Solheim was, by all accounts, a man of conviction. A Depression-era child and former GE engineer, he built his fortune on function over flash. When players like John Daly, Mark Calcavecchia, and Bob Tway left Ping after major championship victories because they wanted guaranteed endorsement money, Karsten wouldn’t budge. His system was a bonus pool based on tour earnings—pure meritocracy.

“In the Karsten years, there were players who left Ping after winning majors, John Daly, Mark Calcavecchia and Bob Tway among them. They wanted the guaranteed payday that comes from being a star golfer, and Karsten, a stubborn Norwegian and a child of the Depression, despised the notion of pay-to-play.”

Now, I’ll be direct: in 1996, when John A. took the reins at age 50, that stubborn approach was becoming a liability. Tour players had leverage. The endorsement market was exploding. Ping risked becoming the equipment choice of former champions rather than current ones.

What John A. did next—implementing a pay-to-play structure that kept Louis Oosthuizen, Bubba Watson, and others in the Ping family—wasn’t a surrender of values. It was pragmatism in service of those values. He understood that maintaining a player roster competitive enough to prove your equipment works is essential to the mission. You can’t evangelize better tools if the best players abandon you.

Three Generations, One Insight

But here’s where the story gets genuinely interesting, and where I think the third-generation leadership—John K., now president and CEO—reveals something his grandfather might have resisted but ultimately would’ve respected.

“Visual and tactile elements of club design — the feel of it, its finish — does in fact influence performance…You do have to feel good about your club in every regard. To like a club, you have to like its look and feel.”

This is not a retreat from Karsten’s function-first philosophy. It’s an evolution of it. In my experience caddying in the early ’90s, I saw firsthand how psychology and mechanics are inseparable in golf. A player carrying a club they love—not just respect, but actually love—performs differently. Confidence matters. Aesthetics influence confidence.

Karsten believed in the engineering. John K. recognizes that the engineering is incomplete without acknowledging the human holding the club. That’s not a contradiction. That’s maturity.

The Bigger Picture: What Ping Gets Right

Over 35 years covering the tour, I’ve watched equipment companies chase quarterly earnings reports and sponsorship contracts. Ping has maintained roughly 1,000 employees with low turnover since Karsten’s era. They’re still family-owned. They still invest in customer service at a level that feels personal rather than transactional.

Look at Ping’s footprint across the sport:

- The Solheim Cup—one of the sport’s marquee international events

- The Karsten Course at Oklahoma State—an investment in collegiate golf infrastructure

- Left-handed equipment—a category Ping has championed when others saw it as niche

- Senior and junior golf—perimeter-weighted clubs making the game more accessible

These aren’t vanity projects. They’re expressions of a coherent philosophy: grow the game, and the business grows with it.

On Nostalgia and Substance

I’ll admit—Bamberger’s personal testimony about his Eye2 irons, the backup sets gathering in his closet, the memories woven into those clubs—could’ve read as sentimental indulgence. Instead, it anchors the bigger argument: loyalty to equipment isn’t irrational. It’s earned through performance, reliability, and emotional resonance.

“Don’t tell me I’d shoot lower scores with other irons, because I don’t believe it and I don’t care.”

That’s not nostalgia talking. That’s competence and confidence. A veteran golf writer with three decades of experience choosing Ping Eye2s isn’t making an emotional argument—he’s making a functional one that happens to *feel* good.

The Real Competition

Here’s what I think matters about this story in 2024: Ping’s competition isn’t other equipment manufacturers anymore. It’s the temptation to treat golf as just another consumer market, where brand loyalty is built through celebrity endorsements and equipment cycles designed to become obsolete.

John A. Solheim, now 80 and stepping back after three decades of stewardship, chose a different path. His son is continuing it. That’s noteworthy. In an era where family businesses often collapse under the weight of succession or the seduction of private equity, Ping remains committed to the proposition that the equipment should improve the game, not just capitalize on it.

Whether that philosophy sustains in future decades, I honestly can’t say. But having watched golf’s business side metastasize into something unrecognizable to the game itself, I’m grateful it exists. Ping reminds us that there’s another way to do this—not perfectly, but conscientiously.

That’s worth paying attention to.