What Golfweek’s 50-Year Run Tells Us About the Game We Love

I’ve spent the better part of four decades watching golf evolve from a sport covered by newspapers to a multimedia empire spanning every platform imaginable. In that time, I’ve learned that the most important publications aren’t always the flashiest ones—they’re the ones that understand something fundamental: golfers are obsessively interested in other golfers, whether they’re major champions or weekend hackers trying to break 80 at their home course.

Reading Tom Stine’s reflections on Golfweek’s 50-year journey reinforced why that publication has mattered so much to this game. It wasn’t built on celebrity gossip or hot takes. It was built in a garage by a newspaper man and his golf-loving wife, armed with a radical idea: publish every name, every score, no exceptions.

That might sound quaint now, in the age of instant updates and live leaderboards. But here’s what strikes me about that philosophy—it was democratic in a way that golf coverage had never been before.

The Democratization of Golf News

Charley Stine understood something his competitors at Golf World didn’t: that the aunt in Pittsburgh cared just as much about seeing her nephew’s name in print as the golf industry cared about Jack Nicklaus’s latest tournament victory. Both mattered. That insight—that completeness was a feature, not a bug—built the foundation for everything that followed.

“Our attitude was exactly the opposite. Every name would be in there. Consequently, we had mothers and fathers and brothers and grandmothers and aunts and uncles who wanted to subscribe to Golfweek because their nephew or their niece or their grandson was playing in some junior tournament in Pittsburgh and they got to see his name in print, even if he finished way down the list.”

I’ve caddied, I’ve covered tours, and I can tell you that this approach created something invaluable: it made junior golfers feel like they were part of something bigger. It gave them legitimacy. Paul Azinger grew up reading those agate pages, hunting for his name, building the identity that would eventually make him a star. He wasn’t unique in that regard—he was just the one who made it to the PGA Tour.

The point is, Golfweek didn’t wait for players to become famous to cover them. It covered them on their way up, and that created a loyalty that transcended typical magazine subscriber relationships. This was before social media, before the internet. This was a different kind of community.

The Unglamorous Reality of Building Something That Lasts

What I found most refreshing about this interview is Tom Stine’s honesty about the struggle. These weren’t venture capitalists with deep pockets. These were people who literally drove to the Masters, filed stories while driving back through the night, processed their own film, and delivered papers to the post office at midnight to make deadlines. By modern standards, the chaos seems almost incomprehensible. By any honest standard, it was incredible work.

“It was hair on fire every week. I remember the first time we got credentials to go to the Masters and dad and I went, and one other writer that we had at the time…we had to go to press on Monday. So, the three of us drove up there. As soon as the tournament was over, we got in the car and headed for Winter Haven. And dad and our other writer started writing and I drove.”

In my experience covering the tour, there’s a temptation to mythologize the early days—to make them sound more romantic than they were. But Stine doesn’t do that. He’s clear: they worked constantly, made little money, and poured everything back into the operation. They succeeded not because of luck or inherited advantage, but because the concept was sound and they executed with discipline.

That’s an increasingly rare story in media. More rare still is the recognition that knowing when to step away matters just as much as knowing when to push forward. When Stine says they were “worn down” and “needed to sell it,” he’s not admitting defeat. He’s describing maturity. They’d built something valuable, served its purpose, and passed it to someone else who could take it forward. That takes wisdom.

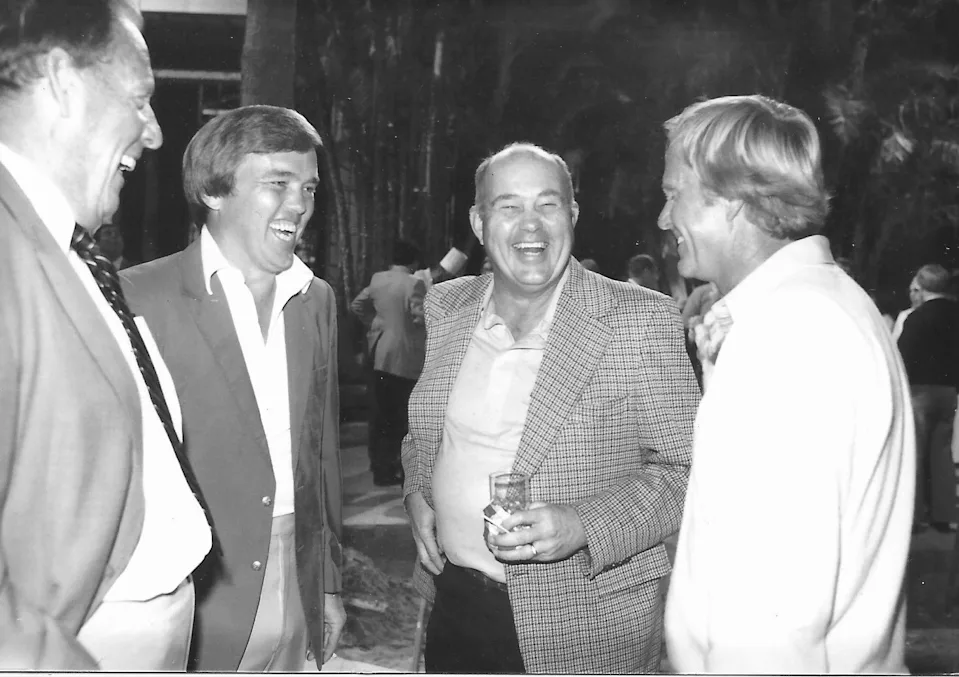

The People Who Made It Work

Here’s something else that stood out to me: the absolute reverence Stine has for his team. Not just for his father, but for James Achenbach and especially Ron Balicki. When Stine talks about Balicki, his emotion is genuine. He acknowledges Balicki wasn’t the most technically skilled writer, but notes that “God made copy editors” for that reason. What mattered was that Balicki cared about people—genuinely, authentically—and that came through in his work.

“He was absolutely genuine about liking them and getting to know them and getting to know their parents…Everybody who knew Ron Balicki loved Ron Balicki. He’s one of the finest individuals I have ever known.”

That’s the ingredient no MBA program can teach. That’s the thing that separates publications that last from those that fade. You need people who actually love the subject and the community they’re serving. Balicki wasn’t pretending. Neither was David Leadbetter when he was teaching mini-tour players off the back of a range at Greenleaf, back when nobody had heard of him. That authenticity builds something real.

A Question for Today’s Golf Media

As someone who’s watched golf coverage evolve from weekly magazines to 24-hour digital cycles, I wonder if we’ve lost something in the translation. Stine himself admits he doubts Golfweek publishes “as thorough a job of publishing every name and every score” anymore. In an age of unlimited digital real estate, that seems impossible to excuse.

The fact that this magazine has survived fifty years isn’t surprising to me. What matters is whether it—and all of us covering this game—remembers why it was worth surviving for: because golf matters to everyone who plays it, not just those playing it at the highest levels.

That lesson from a garage in Winter Haven, Florida, is worth remembering.